04 Stop Collecting. Start Filtering.

Collecting feedback is easy. The real work is deciding what matters.

Most product teams are collecting more feedback than ever.

Support tickets, user interviews, feature requests, Slack channels, community forums, sales calls, Reddit, review sites. We’ve automated most of it. Nothing slips through.

But then you sit down to decide what to build next and realize: you have thousands of data points and no clear answer.

Collection isn’t the hard part anymore. It’s figuring out what any of it actually means.

More Data, Worse Decisions

We hit this about two years ago.

We’d built all the right systems. Automated feedback collection across support, community, and user conversations. Everything got captured, tagged, routed. We had dashboards showing request volumes by feature, sentiment analysis, the works.

Then someone asked: “What should we build next?”

We had thousands of data points. No clear answer.

The issue wasn’t missing feedback. It was that we treated all feedback the same. A feature request from one user got the same weight as a recurring pain point from hundreds. Strategic signals about market shifts sat in the same backlog as minor UI tweaks.

We were drowning in data and starving for insight.

Not All Feedback Is Equal

In the early days, we used to do this. Collect everything, then count our way to decisions. “This feature has 47 requests, that one has 23, so let’s build the first one.”

It feels objective. It’s not. You’re just letting the loudest voices decide your roadmap.

Feedback breaks into types that matter differently:

Strategic signals tell you about market shifts, competitive moves, or fundamental changes in how people work. These don’t show up as feature requests. They show up as context in conversations, throwaway comments about what else people tried, frustrations with entire categories of solutions.

Feature requests are what people explicitly ask for. These are easy to collect and easy to count. They’re also the most misleading. People ask for solutions, not problems. They request features based on what they know, not what they need.

UX friction is what stops people from getting things done. These often come as bug reports or support tickets, but they’re not bugs. They’re design problems. The feature works, but people can’t figure it out or it takes too long.

Bugs and technical issues are their own category, but they tell you something about product quality and where your assumptions break. A cluster of bugs in one area often means the design is fundamentally wrong, not just poorly implemented.

Jobs to be done are what people are actually trying to accomplish. These rarely show up as direct feedback. You have to infer them from behavior, from workarounds, from what people do instead of what they say.

If you process all of these the same way, you’ll build a mess.

A Process That Works

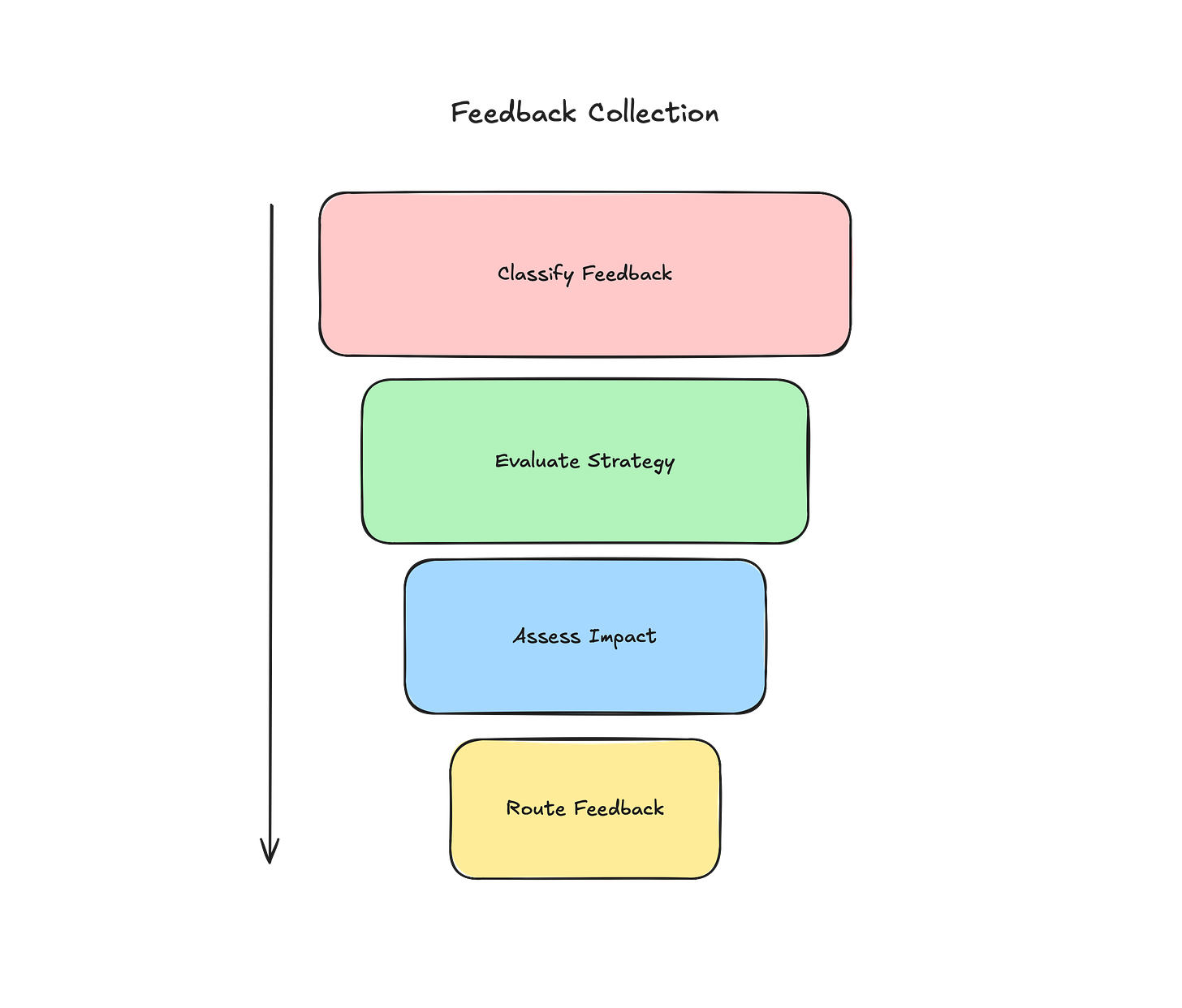

We built something similar to how we handle bug reports. Different paths for different feedback types, routing based on what each piece tells us.

Here’s what we ended up with.

First: Classify by type

Every piece of feedback gets tagged: Strategic signal, feature request, UX issue, bug, competitive intel, or jobs insight. This isn’t automatic. Someone has to read it and think about what it actually means.

Second: Evaluate against strategy

This is the step we kept skipping early on. It felt optional.

It’s not. If feedback doesn’t connect to your strategy, it doesn’t matter how many people want it. Park it. Don’t waste time analyzing something you’re not going to build any soon.

At Localazy, our primary strategy was about making localization work for developers, not translators. When we get feedback about translator workflows, we evaluate it differently than feedback about API integration. Same volume, different relevance.

Third: Assess impact and frequency

For feedback that aligns with strategy, now you look at scale. How many people hit this? How often? What’s the cost of ignoring it?

But “number of requests” is the wrong metric. Ten requests from users who barely use your product means less than two from users who live in it daily. Sales feedback about why deals fell through weighs differently than community requests for nice-to-haves.

Fourth: Route to the right place

- High impact + strategic fit → Product backlog, prioritized with other work

- Medium impact + strategic fit → Backlog for later

- Low impact or unclear → Parking lot, reviewed quarterly

- Doesn’t fit strategy → Ignore, document why

Most of this can be automated. Tools like Dovetail can classify feedback types, surface themes, and route things based on rules you set. The automation gets you 60% there.

What can’t be automated is the thinking. Deciding if a theme actually matters for your strategy. Figuring out if ten requests represent a real problem or just ten different ways of asking for the same misguided solution. Knowing when to dig deeper and when to move on.

That’s where the process helps. It structures your thinking so you’re not spending time on feedback that doesn’t matter.

The Strategy Problem

You need strategy to filter feedback. But you need feedback to inform strategy. Which comes first?

I’ve never figured out a clean answer. It’s messy and circular.

What seems to work: start with a hypothesis about what matters. Your hunch about the market, the problem, the solution. Use feedback to validate or challenge it. That shapes the next version of the strategy. Which changes how you filter the next round of feedback.

Some teams lock down their strategy too early. “This is our strategy, so we ignore anything that doesn’t fit.” That’s how you miss important signals when the market shifts.

Other teams never commit to a strategy. “We’ll listen to users and let them tell us what to build.” That’s how you end up building whatever’s requested most recently.

I try to stay somewhere in between. Strong opinions, loosely held. A clear point of view about what matters, with the willingness to change it when evidence says we’re wrong. Sometimes you get this right. Sometimes you don’t.

The Scale Problem

When you’re small, you can read every piece of feedback. Someone remembers that three users mentioned the same pain point in different ways. Context lives in people’s heads.

As you grow, that breaks. You get too much feedback. No one person can track it all. Context gets lost. Teams start counting requests instead of understanding problems.

You need systems that scale. Not just collection, but processing. Clear criteria for what gets attention. Structured ways to extract themes. Regular review cycles instead of continuous triage.

The part most teams hate? Ignoring feedback.

But you need a bias for ignoring. Not everything deserves deep analysis. Most feedback should be understood, captured and stored, but the goal isn’t to respond to everything. It’s to find the signal that matters and act on it.

Thematic Analysis That Helps

When people talk about “thematic analysis,” they usually mean one of two things: the formal academic method or some vague process of “looking for patterns.”

Neither seems to work well in practice.

The academic version takes too long. You’re not writing a research paper. You need to make decisions this quarter.

The vague version produces nothing useful. “We saw some themes” isn’t insight. It’s just pattern matching on whatever you already believed.

What should you do instead?

Batch your feedback. Don’t analyze every day. Set a cadence, weekly or biweekly. Collect everything that came in, then process it together.

Read for problems, not requests. When someone says “I want a dark mode,” the problem isn’t “no dark mode.” It’s “I use this at night and it hurts my eyes” or “I want this to look professional in screenshots” or “I like dark mode.” Those are different problems with different solutions.

Code by job, not by feature. Don’t group feedback by what people asked for. Group by what they’re trying to do. All the feedback about API integration, developer setup, and CLI tools might be the same theme: “I want to use this without leaving my terminal.”

Stop when you have enough. You don’t need to code every piece of feedback. You’re looking for patterns that appear multiple times across different sources. Once you see the same theme in support, community, and sales conversations, you have enough. More won’t change the insight.

Document your themes, not your counts. Don’t write “47 users requested X.” Write “Users struggle to onboard their team because they don’t understand roles and permissions upfront.” One is a feature request. The other is a problem worth solving.

What We Actually Do

At Localazy, we use Dovetail for most of this work.

User interviews go into Dovetail first. We capture the recordings, transcripts, key moments. Then we do the analysis there. Tag themes. Link related insights. Connect feedback across different conversations.

The real value comes from channels. We pipe Intercom and our community discussions into Dovetail. It does automated thematic analysis based on high-level topics we define. We set the topics with descriptions like “Developer onboarding pain” or “Translation workflow friction.” Dovetail surfaces subthemes automatically.

This doesn’t replace thinking. It replaces the manual work of reading 200 support conversations to find patterns. We still evaluate what matters. We still decide what connects to strategy. But we’re not starting from scratch every time.

We create insights from these themes. Each insight links back to the individual conversations. So when someone asks “Why are we prioritizing API improvements?” we can point to twelve conversations across support, community, and user interviews that all hit the same problem.

Bugs flow through a separate process, but they feed into the same analysis. A bug cluster in one area often reveals a deeper problem. If we’re seeing repeated issues with team permissions, that’s not just bugs. It’s a sign the whole model is confusing.

We’ve thought about using opportunity-solution trees to map this. Connect outcomes to opportunities to solutions. In theory, it makes sense. In practice, we’re not sure the overhead is worth it. The tree structure might help visualize connections, but we already see those connections in Dovetail. Adding another framework might just be more ceremony.

Once every two weeks, we spend a morning going through it all. Three of us: me, the design lead, and someone from engineering.

We look at what Dovetail surfaced. We read the insights. We check if themes connect to our strategy. We look for patterns across different sources. Not “how many people said this” but “is this showing up in different places?”

We route it. Backlog, parking lot, or ignore. We document why for each.

The whole thing takes two hours. The tool handles aggregation and pattern detection. We handle judgment and prioritization.

This system isn’t perfect. We’ve parked things that turned out to matter. We’ve prioritized things that didn’t. But it’s fast, it’s clear, and it keeps us from drowning in data.

The Part We Still Struggle With

The process itself isn’t hard. Tools like Dovetail make the mechanics easier. Classification, evaluation, routing. You can build this in a week.

What’s hard is saying no.

Parking feedback from important customers. Ignoring requests that show up repeatedly but don’t fit your strategy. Telling people who gave you detailed, thoughtful feedback that you’re not going to build what they asked for.

We’re still not great at this. Sometimes we cave and add things to the backlog that don’t really fit. Sometimes we ignore things we should have paid attention to.

But the teams we’ve seen ship coherent products all seem to filter aggressively. They say no to most feedback most of the time.

It feels wrong. But we haven’t found another way that works.

Where You Could Start

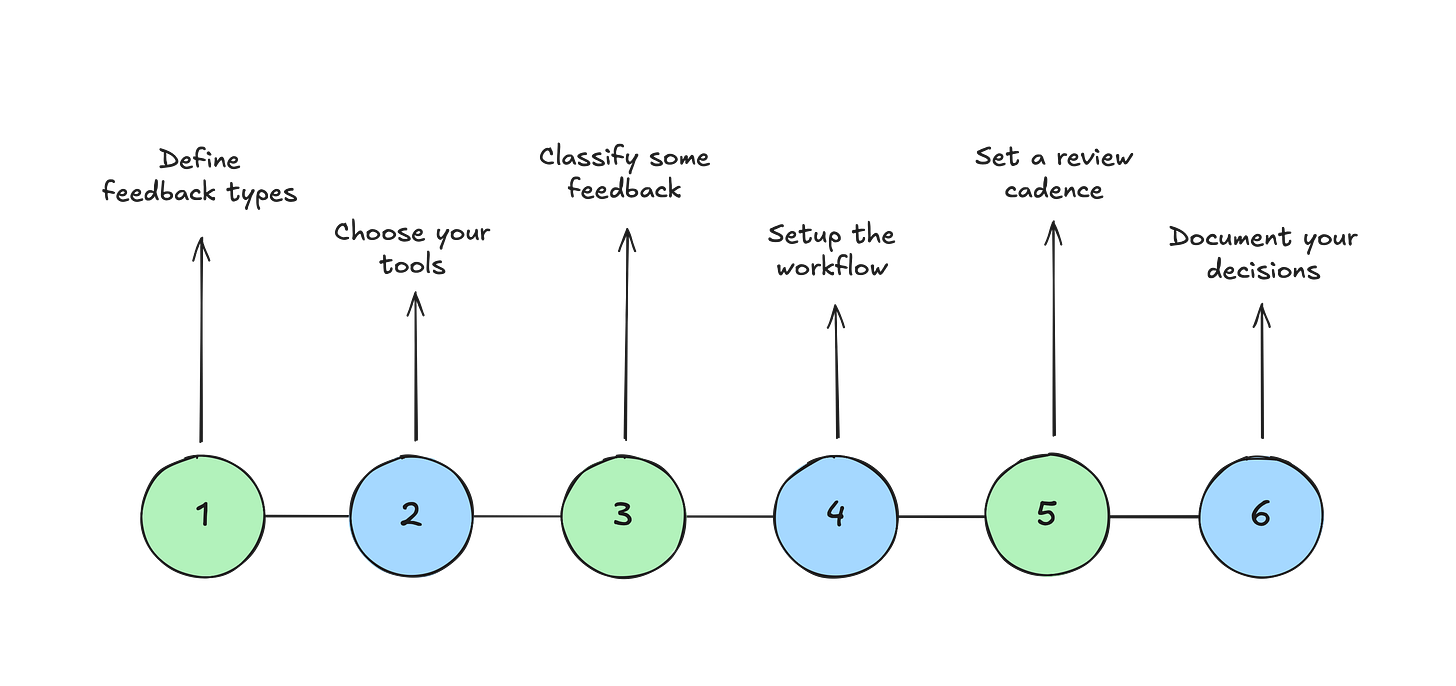

If you’re drowning in feedback like we were, here’s what helped us:

Stop worrying about collection. You probably have enough data. The problem likely isn’t coverage.

Define your feedback types. Write down what counts as strategic, what’s a feature request, what’s friction, what’s a bug pattern, what’s noise. Get your team to agree. We spent half a day on this and still reference that doc.

Choose your tools. We use Dovetail. You might use something else. The tool matters less than having one place where feedback lives and gets analyzed. Spreading it across six different systems made everything harder.

Pick ten recent pieces of feedback. Classify them. Evaluate them against your strategy. Route them. See where you disagree and why. This will show you where your process breaks.

Build the workflow. Capture, classify, evaluate, route. Connect your support tool, your community platform, your interview recordings. Set up the automation to surface patterns, not just collect data.

Set a review cadence. Weekly works if you’re small. Biweekly if you’re bigger. We tried monthly and lost too much context between sessions.

Document your decisions. Not a detailed record of every piece of feedback. Just why you prioritized what you did and why you parked what you didn’t. This helps when someone asks six months later why you ignored their request.

The Real Work

Collecting and categorizing feedback is easy now. Tools have solved that problem.

The work isn’t in processing. It’s deciding what matters. Saying no to most things so you can say yes to the right ones.

There’s no framework that solves this for you. You have to understand your strategy, know your users, and make judgment calls.

But you can build systems that make those judgment calls a bit easier. That surface the right information at the right time. That help you separate signal from noise.

We’re still learning what works. But at least we’re not drowning anymore.